Words, Words, Words!

Assessing & Addressing the Vocabulary Gap

By Allison Sedey, Early Language Outcomes lab (ĒLO), University of Colorado-Boulder

Importance of Vocabulary

“Mama”, “dada”, “ball”, “bye-bye” – whether it is one of these common early words — or something more unique — witnessing your child saying or signing their first word is an exciting moment! Words – spoken and/or signed – are critical building blocks for communication and reading skills. Research over many years has supported a significant relationship between vocabulary and reading comprehension in school-aged children (Clarke et al., 2010; Muter et al., 2004). Additionally, a toddler’s vocabulary size at 2 years of age predicts how well they will read and understand written material in elementary school. (Duff et al., 2015; Lee, 2011).

Because vocabulary is so important, it is helpful to understand how word learning typically progresses. Understanding typical milestones allows us to monitor a child’s language development and set appropriate expectations.

How Vocabulary Grows

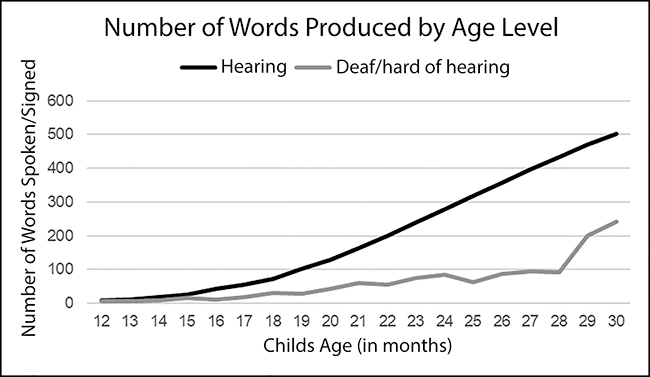

Children typically produce their first word between 8 and 14 months of age, adding approximately five to ten new words to their vocabulary every month up to 18 months of age. At approximately 18 months, children markedly increase their rate of vocabulary learning, producing 30 to 40 new words every month. This means that by 2½ years old, on average, children have an expressive vocabulary of 500 words (with 80% of 2½-year-old children producing somewhere between 270 to 640 different words) (Marchman et al., 2023).

Vocabulary Development in Children who are Deaf/Hard of Hearing

What does vocabulary growth look like for young children who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing (D/HH)? That is a question our Early Language Outcomes (ĒLO) team has studied in collaboration with early intervention programs in 15 states. We used the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories (MB-CDI, Marchman et al., 2023) to measure vocabulary skills, and we collected over 1,000 assessments from children with bilateral hearing differences and no other conditions affecting language development.

The good news: Young children who are D/HH begin their word-learning journey much like children with typical hearing. Many say/sign their first word by or before 14 months of age and add about four to five new words each month until 18 months.

However, word learning challenges can become apparent as children move into their toddler years. On average, D/HH children say/sign about 15 new words per month—fewer than the 30-40 words gained by their hearing peers. (See the “number of words produced by age level” chart.) Over time, this slower rate creates a vocabulary gap.

Don’t Guess – Assess!

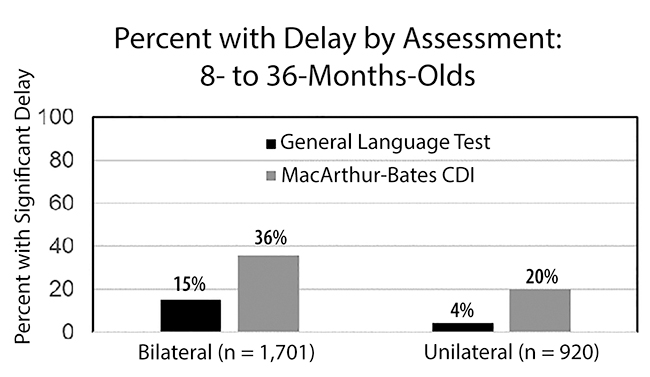

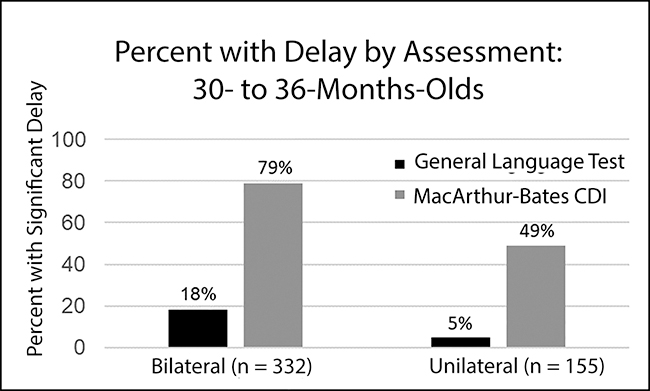

It’s very difficult to tell if your child’s vocabulary is growing as expected just by gut feeling or observation. A language assessment administered by a qualified professional can add valuable objective information about a child’s vocabulary skills. Yet not all language assessments are created equal.

General language assessments may miss language gaps if they are not specific about what counts as a correct response. For example, for a test question such as “child tells you what he is doing” equal credit would be given for the answers “eat” and “I’m eating a turkey sandwich with Swiss cheese” even though clearly, these responses show very different language levels. Additionally, general language tests may give points for early, non-verbal communication skills such as “cries when hungry or uncomfortable” and “points to things”. Children who are D/HH typically develop these skills at the expected ages, and credit for these items may buffer their score pushing it into the average range even when delays in spoken or sign language exist.

Comparing a commonly used general language test to a more specific vocabulary assessment (the MB-CDI), our team found that considerably more children were identified with language delay when the MB-CDI was used. As shown in the “Percent with Delay” bar graphs, this was especially true as children approached preschool age (i.e., 30 to 36 months). This is crucial for determining whether a child needs extra support as they start school. General language assessments may underestimate a child’s needs, whereas a specific vocabulary assessment such as the MB-CDI is more likely to identify language gaps if they exist. Plus, the MB-CDI is available in Spanish and ASL, making it accessible to more families.

Closing the Vocabulary Gap

What can parents and professionals do to maximize children’s vocabulary growth? These evidence-based strategies can help:

Frequency of Input

Common sense tells us that children cannot learn a word they have never seen/heard. Repeated exposure to new words is key. In keeping with the “once is not enough” philosophy, multiple studies have found that the number of times a child is exposed to a word impacts if and how well the word is learned (Ambridge et al., 2015; Gershkoff-Stowe & Hahn, 2007; Goodman et al., 2008; Storkel et al., 2017). If you are introducing a new word like “family”, use it multiple times in many contexts. At the dinner table: “Our family is eating together tonight” At a school event: “How many families are here today?” Reading a book: “There are two girls in their family.”

Limit “Repeat After Me”

It is tempting to think that asking a child to repeat new vocabulary will enhance word learning; however, the jury is still out on the effectiveness of this practice with children. While some studies have found that imitation improves a child’s ability to learn a word (Kan et al., 2014), others have found no significant differences in word learning between an attend-only condition and an attend-then-produce condition (Richtsmeier et al., 2024). Some researchers have reported a “reverse production effect” meaning that having the child imitate a new word interferes with word learning, especially in young children (Zamuner et al., 2018). For some children, frequent requests to repeat make learning feel like a chore. Instead, focus on making word learning fun and joyful in everyday life.

Use Visuals

Pairing new words with pictures or objects enhances a child’s word learning (Heisler et al., 2010).

Add Additional Information

There is consistent evidence of additional benefits when new vocabulary is combined with additional language-based information (Gladfelter & Goffman, 2018: Richtsmeier, 2024). You can:

- Define the word: “Magnify means to make something bigger.”

- Pair the word with a known synonym: “The boy is frightened; he is scared.”

- Contrast the word with a known opposite “It’s not big; it’s tiny.”

- Offer examples: “What fruit do you want – an apple, banana, or pear?

- Supply additional details: “That flamingo is standing on one leg.”

By weaving these strategies into everyday interactions, adults can create a language-rich environment that fosters a child’s vocabulary growth. Building a strong foundation of words early on can pave the way for communication, language, and reading success. ~

References:

Ambridge, B., Kidd, E., Rowland, C. F., & Theakston, A. L. (2015). The ubiquity of frequency effects in first language acquisition. Journal of Child Language, 42(2), 239–273. https://doi.org/10.1017/S030500091400049X

Clarke, P.J., Snowling, M.J., Truelove, E., & Hulme, C. (2010). Ameliorating children’s reading comprehension difficulties: A randomised controlled trial. Psychological Science, 21(8), 1106–1116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610375449

Duff, F.J, Reen, G., Plunkett, K., & Nation, K. (2015). Do infant vocabulary skills predict school-age language and literacy outcomes? The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(8), 848-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12378

Gershkoff-Stowe, L., & Hahn, E. R. (2007). Fast mapping skills in the developing lexicon. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50(3), 682–697. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2007/048)

Gladfelter, A., & Goffman, L. (2018). Semantic richness and word learning in children with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Science, 21(2), Article e12543. doi: 10.1111/desc.12543

Goodman, J. C., Dale, P. S., & Li, P. (2008). Does frequency count? Parental input and the acquisition of vocabulary. Journal of Child Language, 35(3), 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0305000907008641

Heisler, L., Goffman, L., & Younger, B. (2010). Lexical and articulatory interactions in children’s language production. Developmental Science, 13(5), 722–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00930.x

Kan, P. F., Sadagopan, N., Janich, L., & Andrade, M. (2014). Effects of speech practice on fast mapping in monolingual and bilingual speakers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57(3), 929–941. https://doi.org/10.1044/ 2013_JSLHR-L-13-0045

Lee, J. (2011). Size matters: Early vocabulary as a predictor of language and literacy competence. Applied Psycholinguistics, 32(1), 69–92. doi:10.1017/S0142716410000299

Marchman, V. A., Dale, P. S., and Fenson, L. (2023). The MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories: User’s Guide and Technical Manual, 3rd Edition. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Muter, V., Hulme, C., Snowling, M. J., & Stevenson, J. (2004). Phonemes, rimes, vocabulary, and grammatical skills as foundations of early reading development: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 40(5), 665–681. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.665

Richtsmeier, P. T., Gladfelter, A., & Moore, M. W. (2024). Contributions of speaking, listening, and semantic depth to word learning in typical 3- and 4-year-olds. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 55(4), 1085-1098. https://doi.org/10.1044/2024_LSHSS-23-00105

Storkel, H. L., Voelmle, K., Fierro, V., Flake, K., Fleming, K., K., & Romine, R. S. (2017). Interactive book reading to accelerate word learning by kindergarten children with specific language impairment: Identifying an adequate intensity and variation in treatment response. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 48(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_LSHSS-16-0014

Zamuner, T. S., Strahm, S., Morin-Lessard, E., & Page, M. P. A. (2018). Reverse production effect: Children recognize novel words better when they are heard rather than produced. Developmental Science, 21(4): e12636. doi: 10.1111/desc.12636

H&V Communicator – Winter 2024/25