Filling the Disability Representation Gap

By Sara Kennedy, H&V Headquarters

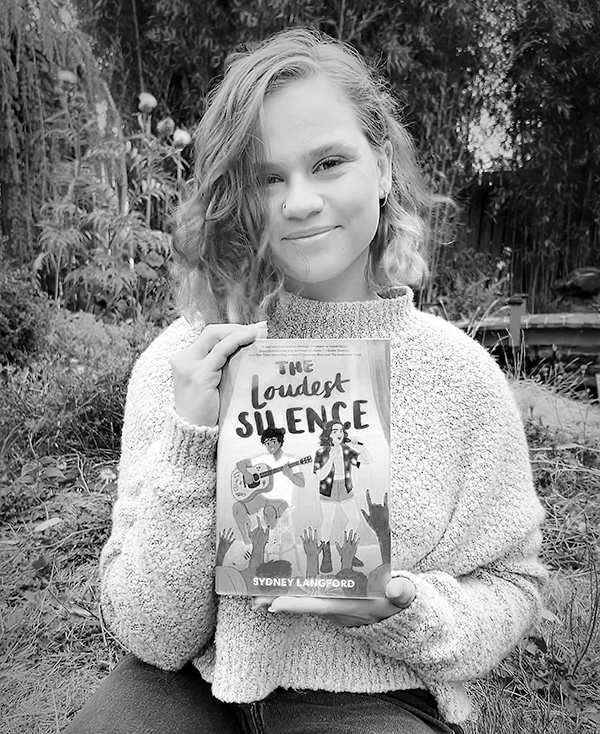

An interview with Sydney Langford, Author

As parents, oh, how we worry about reaching that magic age when kids are reading to learn, and not just learning to read! We know the joy and relief as parents when our kids can finally connect to books that show them new worlds, new concepts, and spur on their thinking when they have mastered reading enough to get lost in a story. Lean in with me as we learn from Sydney Langford, a young adult author who had another idea in mind.

First, a little background. Langford lost about 60% of their hearing at age 14. After becoming Deaf‑Hard of Hearing, they didn’t know where they belonged. They didn’t yet know ASL, nor were they raised in the Deaf community, so they didn’t feel “Deaf enough,” nor “hearing enough” for the hearing world. This experience inspired their debut novel The Loudest Silence.

Q: What first drew you to writing, Sydney?

A: Before I was a Deaf, queer, and Disabled author, I was a Deaf, queer, and Disabled reader. For years after I unexpectedly became Deaf, my solace was found in stories—I’d get lost in books, focusing on fiction as an act of self-preservation as I grappled with my new reality. But the more I read, the less I felt represented. I craved stories that showed the messiness and chaos that comes with being a disabled, queer teen.

On the rare occasion a book had disability represented, it’d be a poorly researched depiction from an abled author or written with an inspiring or tragic angle. That changed when I picked up This is Kind of an Epic Love Story by Kacen Callender, a YA romance between a Hearing and a Deaf character, who used both ASL and voicing to communicate. I’ll never forget how feeling seen by a book felt—a rush of excitement, a deep sense of comfort.

Q: You know I have to ask this since we are a family-to-family support organization: What sticks out to you as helpful/not helpful in the adults around you when you became Deaf? What was that period like for you?

A: My mom and brother were eager to implement accommodations and ease my adjustment. They learned pertinent basic signs (i.e.: “overwhelmed,” “let’s go,” “I don’t understand”), tried to reduce background noise when talking to me, and put captions on all our devices/TVs. Unfortunately, most others tried to act like it didn’t happen and treated me like I was still Hearing, but I was different from my previous abled self and my needs shifted.

Many wanted to avoid the topic because it was uncomfortable for them, but I wish they would’ve just asked how best to support me. We should encourage open conversations about disabilities and accommodations and be willing to adapt to help those we care about.

Q: How does that play into themes and characters in your books?

A: The main characters in my debut novel—Casey, a 16-year-old aspiring singer who grapples with sudden hearing loss; and Hayden, a soccer captain with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and a secret love for music—are pieces of myself split up and redesigned. My lifelong struggle with GAD and the mourning period I experienced post-hearing loss were crucial for me to represent. Especially how lost and stuck between two worlds Casey feels since she’s not fluent in sign and hasn’t had previous exposure to the Deaf community, but she also no longer fits into the hearing world.

I wanted to use my voice to empower, comfort, and open doors; I also wanted to explore the ugly side of being a marginalized teen, the complex equilibrium that exists between Disabled joy and grief, and internalized ableism that can be so hard to untangle. I think of it as providing a window into a Disabled perspective for able-bodied people, and a mirror for disabled people to see themselves represented.

Q: Has it been difficult to find publishers interested in these authentic “light and dark” characters; not just the tragic or inspiring figure more often portrayed?

A: Absolutely. Some wanted the book to skew more toward escapism and lean into funnier elements. Others wanted to dig deeper into the “doom and gloom,” and suggested cutting comedic-relief side characters and lighter-hearted moments in favor of exploring grief and hearing loss arcs.

Media depictions often show disability rep as very black-and-white. Light or dark. But… the light and the dark coexist. Marginalized people have a kaleidoscope of colors. There are dark, lonely moments; bright, shining moments; and an often-unspoken grey area. Our emotions and experiences can be a muddy, jumbled mess. I seek to tell stories that explore the ups and downs of being disabled.

Q: What’s your vision for your next five years of writing and creating?

A: My second novel is a queer YA rom com called Someone to Daydream About and will be published in Summer 2026! The main character is Deaf, and the love interest is neurodivergent. I couldn’t be more excited to show disabled characters getting the swoony love stories and “happily-ever-afters” able-bodied characters have historically received.

The following year, I’ll be releasing my second YA rom-com. I can’t share much yet, but it will absolutely highlight disabled and/or queer characters!

Q: Any thoughts for young people reading this who might be interested in becoming better writers?

A: Read widely within the genre you want to write. Take note of things you like or dislike about someone’s writing style. Think about how you could put a unique twist on a genre/trope—especially if it involves a marginalization you have. Treat every book you read like an opportunity to learn more about writing and grow as an author! ~

Editor’s note: Sydney Langford is a queer, Deaf-Hard of Hearing, and physically disabled author living in Portland, Oregon. When not singing musical theater songs or playing with their dogs, they are passionate about writing stories that celebrate inclusivity and the diverse experiences of queer and disabled teens.

Find Langford on social media @slangwrites and website: slangwrites.com.

H&V Communicator – Fall 2024